For years, the standard work on Yeshua’s deity was a thin book titled The Great Mystery, or, How Can Three Be One? by Tzvi Nassi. Valuable though it was, the book suffers from a lack of clear documentation and poor distribution. It has now been eclipsed.

For years, the standard work on Yeshua’s deity was a thin book titled The Great Mystery, or, How Can Three Be One? by Tzvi Nassi. Valuable though it was, the book suffers from a lack of clear documentation and poor distribution. It has now been eclipsed.

A few years ago within the space of a few months I had the privilege of attending the Hashivenu forum in Los Angeles and the Borough Park Symposium in New York. Providentially, the topic of both Messianic Jewish theological conferences was the deity of Yeshua. I was partly surprised and greatly heartened to see the unity in commitment to this central claim that we make for Him. Representatives from around the world and across North America were in agreement. How, though, are we to articulate this aspect of our very Jewish faith in Yeshua as Messiah? In some measure, we as Messianic Jews have fallen short in our ability to do so. We have been able to make arguments from the Scriptures, and we have resorted to various texts and concepts from Jewish sources. Faced with seemingly superior scholarship from those who oppose the idea of Yeshua’s messiahship, some have had their faith shaken.

The Return of the Kosher Pig demonstrates that not only the Scriptures, but also Judaism, has room for the concept of a divine Messiah. In the first part of his book, while holding that the literal, or p’shat, meaning of the Scriptures is foundational, he yet brings proofs from both ancient and modern Jewish sources to make his case according to his conviction ‘that the approach of presenting the true nature of Messiah must go through Judaism and not around Judaism or outside of Judaism’ (27). With this in mind Shapira is respectful of rabbinical scholarship and rulings, but does not assume that they are always correct.

The second part of the book is an examination of that Yeshua’s messiahship implies. If He is not Whom we claim He is, then we Messianic Jews are heretics and idol-worshippers. But the other side of the coin is also true. If He is, then Maimonides’ thirteen articles of faith, cannot be fully accepted as they stand. This is a crucial claim, as these articles are almost universally accepted as the basic creed of Judaism.

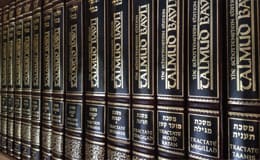

From this point, Shapira moves on to present his evidence in Part Three. Here he brings five arguments for Messiah’s ranking, authority, origin, role as ‘owner’ of Torah, and role as redeemer. Using Scripture, Talmud, Midrash, Kabbalah, Gematria, Jewish liturgy, ancient and modern Jewish sources, over a century of Messianic Jewish scholarship, and the Brit Hadasha, he argues thoroughly and innovatively. Sometimes interacting with ‘anti-missionaries’ he quotes and rebuts their own arguments against Yeshua.

Part Four is in some ways an appendix, as Shapira produces further arguments compiled from various sources, but stressing what he has already shown. This leads directly to his appeal to traditional Jews to examine the evidence and consider the Messiahship of Yeshua, ‘the most kosher king that Israel ever had and will ever have’ (277).

The Return of the Kosher Pig is not for everyone. Some will struggle with its use of a world of Jewish literature that few Messianic Jews know well. Others will possibly find it more in depth than needed. Some of the arguments advanced, such as those based on gematria, will be unconvincing and at times stretched. However, Messianic Judaism has never before produced such an extended, thoroughly researched case for Messiah Yeshua. The Return deserves to be on the bookshelf of every well read Messianic Jew.